Exit Planning for Retiring Nonprofit CEOs

When chief executives start planning for retirement, they must prepare both themselves and their organization for the next step, while continuing to lead the organization.

Don Tebbe, editor/founder, LifeAfterLeadership.com

Smart chief executives — whether they’re running a business or a nonprofit — acknowledge that they will leave their organization at some point. Every job and every career ends in a transition — eventually. It’s just a matter of when, how, and how well managed they end.

When chief executives retire — especially if they are founders, long-tenured executives, or transformational leaders — their organizations need to devote appropriate time and resources to managing the transition. The longer a chief executive has been in place, or the more significant his or her impact, the harder he or she is to succeed and the more challenges the successor will likely face. An exit plan can help pave the way for a smoother transition.

The ideal time to begin exit planning — especially for longtenured or founder executives — is several years ahead of the retirement date. (Even if only a few months, or perhaps weeks, remain on your tenure, some exit planning can be beneficial.) Many nonprofits fail to plan effectively, typically because either the chief executive did not declare his or her intentions early enough, or more commonly, because the chief executive and/or board failed to recognize the importance and complexity of this critical organizational change.

Chief Executives Have Three Jobs To Do

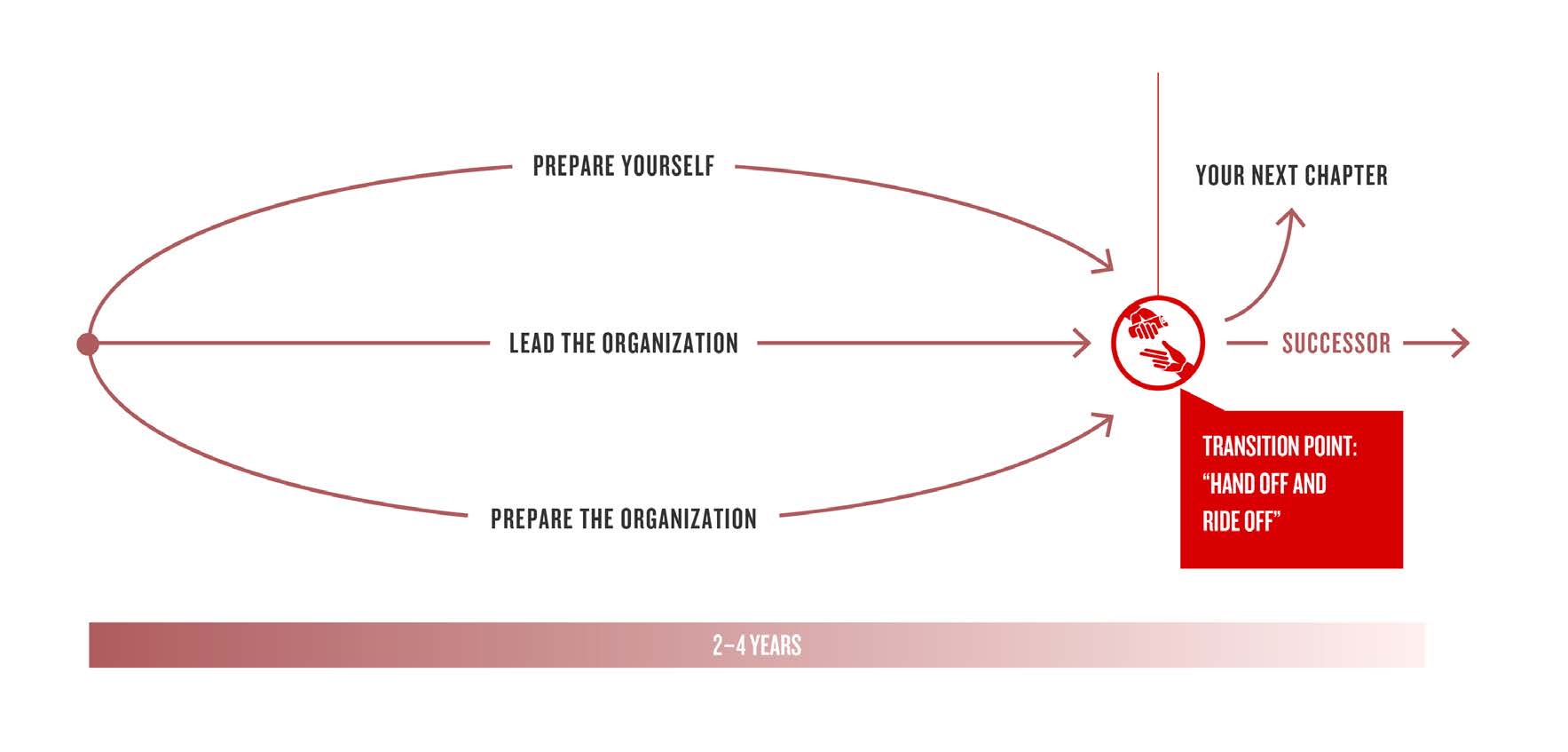

Although you’ll never find it in the job description, the reality is that chief executives have essentially three jobs to perform as they move toward retirement. Job one is, of course, continuing to lead the organization, but that role is going to change. You also have two new jobs:

- Prepare the organization: help ready the organization for the transition and pave the way for your successor.

- Prepare yourself: accommodate yourself to the role of “transitioning leader” and prepare for the next great stage of life.

To help address these two “new jobs,” an exit plan has two preparation tracks: one focused on the chief executive and the other one on the organization. The content of the plan depends on a variety of “readiness” factors — both the chief executive’s readiness as well as the organization’s.

Figure 1 illustrates these three jobs.

Job #1: Lead the Organization

Certainly your primary job is to lead the organization, while recognizing that, as a leader in transition, your role is going to evolve as the transition unfolds and as your departure date draws closer. Chief among those adjustments is maintaining a sense of control while encouraging greater engagement by your board and executive team during this unique moment in the organization’s history. This includes

- encouraging the board to step up and get engaged in the succession and transition planning process, obviously with you helping to inform the members

- letting the board take charge of the selection of your successor and engage in a robust selection process (without undue influence on your part)

- supporting the senior management team in assuming more leadership, especially in preparation for its role in onboarding your successor

Job #2: Prepare Yourself

Executive readiness has several dimensions:

- Commitment to a date – Do you plan to retire in a few months or a few years? That will drive the planning. Sometimes, for a variety of reasons, chief executives are reluctant to set a specific date. Picking the date, however, is necessary to anchor the planning, even if that date is a range (e.g., Summer 2017).

- Professional timing – For most organizations and CEOs, there’s never a “perfect” time for an executive transition, only times that are better than others. For example, it’s usually better to make a transition after a known pivotal event, such as the completion of a capital campaign or the award of a major contract.

- Personal timing – Retirement timing should also take into account your personal life. Get a firm grasp on your financial future. Then develop an exciting, engaged future. You’ll do better if you’re moving towards something new rather than leaving something behind. A post-career support network is also crucial as is a regimen to maintain your physical health and well-being.

- Adjusting to the role of transitioning leader – Your transition out of the organization is a process, not an event. Committing to this role is an important set of choices: the choice to take on these two new jobs; the choice to embrace your leadership role even as you encourage the board to step up on the search and transition; and the choice to prepare the way for your successor. Simultaneously, you must encourage the effective management of the transition process without “controlling” it. You must ready yourself to let go of the organization.

Job #3: Prepare Your Organization

Organizational readiness also has several components:

- The organization’s sustainability – Is the organization sustainable in the face of your departure? Is the organization’s viability tied to you being the CEO? If possible, can you ensure that you have one or more viable internal successors? Do you have or can you develop some financial cushion, particularly if you are the principal fundraising “rainmaker” for the organization?

- The board – Does your board have smart, skilled leadership in place to carry it through the transition? Does it recognize the gravity of this decision? Do the members understand that the selection of a new CEO is not just an everyday hiring decision? Is the board prepared to partner powerfully and effectively with your successor, or do the members micromanage or, conversely, too frequently defer to you? If so, what can you do to shift that prior to the transition?

- Senior management team – Do you have a senior management team in place with people who fit the current and future leadership needs? Do they understand the succession and transition process and are they prepared to embrace the transition?

- Succession development planning – What’s the state of succession planning in your organization? A CEO succession policy is a great tool for getting the board thinking about the importance of this transition and how to manage it well. Large organizations can engage in talent management, which strengthens the senior management team and prepares potential successors for the CEO position.

Exit Planning & the CEO Transition

The timing and sequencing of an exit planned transition varies depending on the organization’s circumstances and the CEO’s personal plans. Ideally, this planning should take place two to three years ahead of the planned departure date. Figure 2 lays out the potential progression of the stages of an exit plan and executive succession.

- Private speculation – Early and typically private thinking by the executive. Usually there’s no formal announcement and little discussion outside close circles. At this stage, some sort of a sounding board can be helpful, such as colleagues who have already retired. This stage often includes a private commitment to a target date, e.g., after the completion of an important contract.

- Planning (stealth or open) – With a departure date in mind, the planning can begin. Usually the planning takes place along the two new tracks described above: preparing the executive and the organization. This planning may take place in the open or in stealth mode, with the involvement of the board leadership or not, depending on organizational circumstances.

- Capacity-building actions – In most cases, some organizational capacity-building is advisable. Critical items to consider include (a) the business model, (b) strategic plans, (c) the strength of leadership, both in the executive team and the board, (d) the organization’s resources, and (e) the organization’s culture and operating climate.

- Search & transition planning – Ideally, the board should begin transition planning at least a year ahead of the planned departure date, including a discussion of how it’s going to manage the search and selection process (unless it’s already done this work in developing a succession policy).

- Executive search – The search for a successor is an integral part of the overall transition process and will take up a significant chunk of the timeline. A good, vigorous executive search and selection process will typically take, at the very minimum, four to five months. A year or more is not unheard of in special cases, particularly in arenas or fields where the incoming executive may be working under an employment contract.

- Transition, handoff, and onboarding – Allow for an appropriate period of overlap between the executives. In some cases that may be a few days and, in others, it might be a few weeks. Usually, the most time-consuming element of the handoff is relationships with critical stakeholders. It may be wise for the departing executive and incoming executive to meet with top-level donors and other critical stakeholders.

In most cases, the best approach is to “hand off and ride off.” In practice, this means be available if your successor needs you, but don’t cast shadow on his or her leadership. Organizations will sometimes ask the departing executive to remain employed in an advisory capacity, or sometimes the departing CEO wants to take on another role in the organization. Having an ongoing relationship with the organization must be handled with some caution; for it to work, it has to work for the successor. The incoming executive should not feel constrained by the presence of his or her predecessor. The success of these arrangements usually boils down to attitude and chemistry — your attitude toward the leadership and authority of the new CEO, and the chemistry between the two of you. You need to be prepared to make it work, even if that means leaving the organization.

Communications — Who to Tell and When

The exit plan should also include a communications strategy for disclosing your departure plans — who you will tell and when. There’s more art than science to timing your retirement announcement. Deciding when to break the news can feel overwhelming. It does require an appropriate degree of caution and thoughtfulness, but it doesn’t have to be too complicated.

- Determine the timeline. The timing of the retirement announcement to the board is often shaped by the level of trust between the executive and the board. If there is a high level of trust, you may choose to engage the board as an early planning partner, perhaps several years ahead of the departure date. At the other end of the spectrum, if you feel that the board may respond by trying to force you out prematurely, you might want to hold your disclosure until later, allowing just enough time for the a minimum five- to six-month search, plus time for the board to organize the committee, hire a search firm, and set things in motion.

- Tell the board. Your announcement of your intention to retire is an uncertain moment for the board, so having at least a shell of the exit plan ready serves as an important reassurance. It’s important to strike a balance — make sure the board knows that you have a plan, but don’t elaborate in a way that makes the board feel as though it’s been left out of the loop.

- Engage the senior management team. When to engage the senior management team depends on many variables. How much capacity needs to be improved, particularly within with your current pool of employees? What is the political climate within the organization — will staff be distracted by jockeying to be the successor? If you decide it’s best to wait until immediately before the search is announced, consider talking with the senior management team first, before other staff and stakeholders.

- Alert key stakeholders and the community. In most cases, key stakeholders (major donors, coalition partners, critical referral sources, etc.) are told about the impending transition when the organization is ready to announce the executive search. If your approach to the succession planning is particularly public, then you may announce earlier. As you think about the announcement, consider segmenting your stakeholder list into three or more lists:

- The “A” list — should receive a personal phone call from you (maybe a visit in special cases)

- The “B” list — informed through the announcement letter from the board chair (you might include a personal note from you as a cover to the chair’s letter)

- The “C” list —the larger universe, which will be informed through your newsletter or a media release, etc.

Typical announcement collaterals include a departure announcement letter from the board chair, a more personalized letter from the CEO, a media release, and, in some cases, a set of talking points. A simple communications plan is advisable — half a page to a page at most — that outlines who will inform whom, by when, and in what sequence. It should also name a “designated “spokesperson for the transition process.

Managing Emotions — Yours and Others

You and the people you have worked with closely will experience a range of emotions in light of your departure announcement. Your announcement will undoubtedly trigger some responses. It’s useful to recognize that these responses are not necessarily about you, but are more about your stakeholders, their relationship to the organization, and the basic human desire for continuity and the status quo. Your announcement disrupts that. These reactions are more about people’s feelings than they are about you in particular. Author William Bridges refers to these emotional responses as “the transition,” a psychological process of coming to terms with the changes that are taking place. There’s a Sufi saying that the secret to satisfaction in life is “patience, forbearance and generosity.” It’s also a good prescription for addressing these emotional responses.

Good communication throughout the process goes a long way to provide stakeholders with assurance that the organization will be okay. Your role as leader-in-transition is to ensure those communications take place. Take charge of the exit planning process — too much communication is better than too little.

Coming to Closure

Feeling a sense of closure about a relationship, job, or career that is ending is vitally important for human beings — for yourself as well as for those with whom you work closely. For you as the departing CEO, a solid exit plan that includes a good handoff plan to transfer the reins to your successor will help provide that sense of closure to your tenure with the organization.

Equally important is your constituents’ closure with you. Public rituals can play an important role in providing venues or occasions for marking closure. This needn’t be the perfunctory rubber-chicken-gold-watch dinner. Seek meaningful encounters between you and your constituents that provide them with the space to feel they have closure. Typically this involves some sort of public gathering (or gatherings) that celebrate successes, honor contributions and focus on the high points and turning points for the organization. Infuse these events with fun, creativity, and humor. Spirited celebrations will do much to satisfy that craving for closure that your constituents in particular will be seeking.

Exit Planning for Retiring CEOs

Download the PDF

101 Resource | Last updated: February 21, 2017

Don is also the author of Chief Executive Transitions: How to Hire and Support a Nonprofit CEO, published by BoardSource.